I spent a lot of time working behind bars and would have the following interaction at least once a week:

Customer: “What’s good?”

Me: “What do you think you’re in the mood for?”

Customer: “Well… I like ales and I like lagers…”

At this point I always thought about suggesting they just point at something, because ALL BEERS ARE EITHER ALES OR LAGERS*. (If you’re thinking “What about hybrid styles?”, we’ll get to that later).

The differences between lagers and ales only have to do with the yeast used to ferment them. Other variables like color, alcohol strength and flavor have nothing at all to do with whether a beer is a lager or an ale. This is one of the most common points of confusion for consumers, so I want to make sure that everyone understands the difference. This article will address what happens during fermentation and how lagers and ales are different. Finally, we’ll confuse matters a bit by talking about hybrid styles.

FERMENTATION

An old saying goes that, “A brewer makes wort, but yeast makes beer.” What this means is that everything that the brewer does on the hot side of the brewery where the kettle and mash tun are is production of wort. Wort is the sugary, bitter liquid that the brewer has prepared as a hospitable environment for yeast to feed and reproduce. While the yeast are doing that, we get the bonus of them making us beer.

Simply stated, fermentation of beer is the process by which yeast consumes simple sugar molecules and produces nearly equal parts of ethanol (the tasty kind of alcohol) and carbon dioxide. That’s all the yeast does. It doesn’t care if the wort is light colored, dark colored, etc. It will eat the sugars and make alcohol and CO2. When it’s done doing this it falls asleep and falls to the bottom of the fermenter, just like after Thanksgiving dinner.

So, what makes an ale an ale and a lager a lager?

ALES

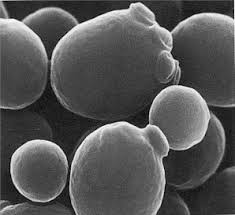

Ales are fermented with different strains of the yeast family

sacchromyces cervisiae or literally “beer sugar fungus”. Within this family there are different strains that have different characteristics. Some strains are very tolerant to alcohol while others are not. Some of these yeast strains produce fruity smelling

esters or spicy

phenols while they eat those sugars and make ethanol and CO2. Some of them are capable of eating longer chain sugar molecules than others. Though they have their differences, they are all considered to be the same species and they all share certain characteristics.

Temperature is the biggest common shared trait and the biggest contrast to the family of lager yeasts. Ale yeasts like to eat sugar at temperatures between 65-75 degrees Fahrenheit, though some ale yeasts might even do the job at slightly cooler or slightly warmer temperatures. Ale yeasts cannot withstand very cold temperatures and most will go dormant below 48 degrees Fahrenheit.

Time it takes to get the job done is another shared trait that is different from lager yeasts. Ale yeasts will typically take about 7 days to finish the primary fermentation of a beer, though they can take up to an additional week or more to completely finish the job. Lager yeasts, as we will discuss, take considerably longer. This is the main reason why many of your favorite craft beers are ales. Small breweries typically don’t have the fermentor space to produce lagers on a regular basis.

Ester production is another way ale yeasts differ from lager yeasts. If you’ve ever smelled banana, pear or juicy fruit gum coming off of your beer, those aromas and flavors were produced by the ale yeast strain that fermented it. Belgian beers are especially known for their fruity and spicy aromas and flavors. These are produced by strains of yeast that Belgian brewers employ that produce a lot of

esters and

phenols. Lager yeasts are not known for producing many esters.

Often the term “top fermenting yeasts” is also used to describe ale yeasts. This goes back to the days before people really had an understanding of how fermentation happened. Before the rise of the microscope in the 17th century, yeast was a bit of a mystery. However, brewers knew that if they took the bubbling

krausen from the top of a fermenter of an actively fermenting batch of beer and put it onto another batch of wort, that wort would start fermenting also. Therefore the beers were considered to be “top fermenting”. In fact, there are yeast all throughout the wort fermenting it from the top to the bottom. The krausen is simply a visible cue that fermentation is happening. Because ale yeast ferment wort rather quickly, the release of carbon dioxide is visible and gets trapped in wort proteins and hop resins to create a frothy layer of foam on the top of the fermenter.

Historically speaking, most ancient beers were produced as ales, as this yeast strain thrives in the same temperature range as humans do in most of Europe. It wasn’t until much more recently that lagers were produced.

LAGERS

Lagers are fermented with yeast belonging to the family

sacchromyces patorianus, sometimes referred to as

sacchromyces carlsbergensis after the Carlsberg brewery where the yeast was first described. Lager yeast is believed to be an ancient hybrid of a wine yeast known as

sacchromyces bayanus and the ale yeast

sacchromyces cervisiae. Within the lager yeast family we see a lot less variety than in the ale family. Lager yeasts are also capable of consuming some sugars that ale yeasts cannot, such as melbiose. Lager yeasts are generally described as “cleaner” than ale yeasts in this respect, and that “clean” character is sought after among lager producers.

Temperature is again of utmost importance to the successful fermentation of a beer with lager yeast. Lager yeasts like to work at much cooler temperatures with the primary fermentation taking place below 50 degrees Fahrenheit. The warm temperatures of an ale fermentation would be detrimental to the health of the lager yeast.

Time becomes a factor after the primary fermentation. The beer is typically cooled to just above freezing and held at that temperature for 6-8 weeks. It is this process that earned the beer family the name

lager as

lager literally means “to store” in German.

It is for this reason that most small breweries do not produce lagers. Small business owners can’t afford to take up valuable tank space for nearly three times as long to produce a batch of beer. Unfortunately, consumers are not willing to pay three times as much for a glass of lager as for a glass of ale.

Ester production is minimal to nonexistent in well produced lagers. The cooler temperatures of the lager fermentation keep the yeast from producing esters or adding any real character of its own to the beer.

In contrast, “bottom fermenting yeasts” is often used to describe lager beer fermentation. What this really is is a result of the cooler fermentation temperature. Yeast metabolism is like many other processes in nature in that the warmer the temperature is the faster it goes and vice versa. Lagers ferment more slowly and though the same materials that create krausen on top of a batch of ale are being produced, they are not as abundant because it is happening so much more slowly. To the brewers who worked before yeast was better understood, it seemed logical that the fermentation was happening at the bottom of the fermenter. This is also where they would find the yeast at the end of the fermentation to be used in the next batch.

The history of lager production is much more recent than that of ales. Though there were some lagers being produced before the 16th century, a 1553 amendment to the famous Bavarian Purity Law of 1516 outlawed brewing in the warm summer months. City leaders were concerned that the beers produced during the summer often tasted sour (due to increased bacteria levels in warm environments). The solution was to only allow beer to be brewed from September 29th to April 23rd each year. Though they didn’t know it yet, they accidentally legislated that only lager yeast could ferment beer in Bavaria, as it was too cold for ale yeast to do well in those months.

HYBRID STYLES

I told you above that I was going to muddy the waters a bit at the end, but even hybrid styles each technically fall into one of the above categories. Hybrid styles are those that use one species of yeast (ale or lager) but are processed like the other species.

For example, Kolsch style ales are native to the region around Cologne, Germany. They are fermented with an ale yeast strain that likes the cooler end of the ale temperature spectrum and are then lagered for several weeks before they are packaged. The result is a crisp, clean, clear beer with very few esters.

On the other hand, the California Common style, popularized by Anchor Brewing of San Francisco, California, is produced with a lager yeast fermented at the cooler end of the ale temperature range.

CONCLUSION

From the discussion above I want to make abundantly clear that there are a wide range of ale and lager styles. Some ales can be very light in color and low in alcohol like the American Cream Ale, and some lagers can be very dark and high in alcohol like the Baltic Porter. Americans typically think of lightly colored, low alcohol beers when we think of lagers, because the beers of the larger commercial breweries in the US are all lagers and all fit that description. However, all of the contributing factors that make a beer dark or high in alcohol are done before yeast is added to the wort. The species of yeast used and the way the beer is fermented determine whether or not the beer is an ale or a lager, nothing else.

If you’d like to learn more about fermentation, join us on a

Brewery & History Walking Tour!

* If you were thinking about beers fermented with Brettanomyces, that will be covered in another post.